As the Texas Supreme Court pointed out in LAN v. Eby[1], construction cases are particularly well suited for the application of the economic loss rule because construction projects operate by agreement and the parties are in a position to protect themselves through negotiation. The economic loss rule is based on a policy judgment that intends to respect the bargains that businesses enter into, requiring contracting parties to seek their remedies from the parties with whom they have contracted as opposed to reaching up the contractual chain.[2] However, the Chapman[3] case and its progeny have opened the door for clever plaintiff’s attorneys to sue each subcontractor directly and avoid application of the economic loss rule.

The economic loss rule generally precludes recovery in tort for economic losses resulting from a party’s failure to perform under a contract when the harm consists of only economic loss of a contractual expectancy.”[4] Specifically, recovery on tort theory may be maintained only when: (1) the duty allegedly breached is independent of any contractual undertaking; and (2) the harm allegedly suffered is something more or other than mere economic loss under a contract.[5] The courts have since clarified that duty by holding that “the negligent performance of a contract that proximately injures a non-contracting party’s property or person states a negligence claim.”[6]

In a negligence action, where property damage occurs collateral to the property that was the subject matter of the contract, the collateral property damage is recoverable under a negligence theory and is not subject to the economic loss rule.[7] The instinctual interpretation of “other” or “collateral” property encompasses property outside of the subject of the construction project.

For example, if a contractor is excavating a roadway and strikes a water line, the contactor has caused damage to occur to collateral property which is clearly outside of the scope of the contract. However, Plaintiff’s attorneys are now crafting pleadings to create the illusion of “collateral damage” when the property damaged is not a subject of your contract, but rather is other work occurring simultaneously on the same project. This article will discuss the ways this “collateral property” standard has been extended and the possible safeguards to its application.

The most common way plaintiff’s attorneys are manipulating their pleadings is by attempting to create a cause of action in negligence by claiming injury to “other work” is injury to “other property.” For example, during construction, a window contractor walks on, and damages, a new roof. The damage to the roof is considered damage to “other property” and the plaintiff will attempt to place full liability on the window contractor using those damages. Chapman set the stage for these pleadings by extending the separate injury standard without providing much reasoning for its extension.[8]

While this type of liability may be warranted in certain situations, such as the window contractor damaging a new roof, plaintiff’s attorneys are now trying this theory far beyond the bounds of anticipated application. Consider the following hypothetical:

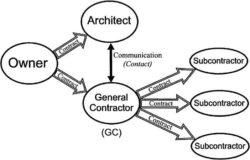

General contractor contracts with owner for the construction of a storage facility. Subsequently, general contractor subcontracts various portions of the work to separate subcontractors including engineering (“Subcontractor A”), erection of structure (“Subcontractor B”), laying of foundation (“Subcontractor C”), manufacturing (“Subcontractor D”), etc. (evidenced by Figure One[9]). After completion of construction, the facility experiences water intrusion which allegedly causes damages to the concrete flatwork, foundation, interior slabs, walls, insulation, and other structures.

Typically, in the hypothetical, owner would bring a lawsuit against general contractor to recover damages for the defective construction of the facility. General contractor would then seek damages from the subcontractors for their respective allegedly defective work. In the wake of the failure to apply the economic loss rule, however, owner now claims damages against each subcontractor directly seeking full recovery of the damages to the entire structure from each subcontractor. Accordingly, owner brings a cause of action against Subcontractor B, claiming its negligent installation of gutters and downspouts lead to improper water intrusion and, ultimately, damage to the foundation, slabs, and entire structure.

Owner avoids the application of the economic loss rule by asserting: (1) that Subcontractor B had an independent duty to construct the storage facility with reasonable care, and (2) it seeks recovery for property damages other separate from the benefits it expected to receive in its contract with general contractor. Specifically, owner suffers loss of use and profits from the facility for its particularly designed purpose as well as damage to the real property, itself, and improvements thereon. Therefore, Subcontractor B is exposed to liability for the entire amount of damages to the structure, whether caused by its work or not.

Subcontractors are not the only ones facing unexpected liability for damages through the avoidance of the economic loss rule. In Zbranek Custom Homes, the Chapman ruling was employed to assist in creating a legal duty owed by a general contractor to the lessees of a home.[10] In Zbranek, Zbranek built a home which was later destroyed in a fire.[11] Zbranek built the home pursuant to a contract with the home’s owner, Bella Cima Developments, L.P.[12] Zbranek, as the home’s general contractor, engaged various independent contractors to perform different aspects of the construction, including the framing, stucco, and masonry.[13]

Under its contract with Bella Cima, Zbranek was responsible “for performance of all duties reasonably necessary to complete the Project” and ensuring that the construction complied “with all applicable laws, codes and ordinances” and was in “substantial compliance with the plans and specifications” of the architect.[14] Bella Cima leased the completed home to the plaintiffs.[15] The home’s plans called for an outdoor fireplace, which was the origin of the house fire upon its very first use following construction.[16] The fire investigator concluded the house fire was caused by the fire in the fireplace igniting combustible materials located within the “void space” between the firebox and the framing materials.[17]

The plaintiff sued Zbranek alleging negligence, as well as several of the subcontractors who performed work during the home’s construction, some of whom were later non-suited or removed from the lawsuit by way of summary judgment.[18] The trial court rendered judgment in plaintiff’s favor and ordered that they recover damages from Zbranek in the amount of $715,420 for loss of personal property and repair costs.[19]

In its affirmation of the judgment, the Austin Court of Appeals cited Chapman to state “there is a common-law duty to perform a contract with care and skill, and the failure to meet this implied standard might provide a basis for recovery in tort under appropriate circumstances.”[20] The Court went on to extend this duty to general contractors, citing the “duty applies to general contractors to ensure that their subcontractors perform their work in a safe manner if the general contractor specifically retains some control over some portion of the work performed by a subcontractor or actually exercises control over the work.”[21]

The Court held Zbranek was fully liable to the plaintiffs by reasoning he exercised control over the construction of the fireplace, therefore he owed a legal duty to construct the fireplace with reasonable care.[22] Therefore, the Chapman ruling is being utilized not only to create liability from a subcontractor to an owner, but from a general contractor to subsequent lessees as well.

A common theme among the cases which avoid the economic loss rule is the inadequacy of an alternative remedy. Specifically, many cases involve situations where all other parties have been dismissed – through non-suit or summary judgment – or the general contractor carries an insurance policy which is insufficient to cover the damages sought. Although it has been expressly stated that this is not a permissive basis for avoidance of the application of the economic loss rule[23], the lack of alternate remedy is likely a factor that plays in the trial judge’s decision.

Thus, subcontractors should ensure their general contractor holds an insurance policy which equals or exceeds the cost of the project. Further, subcontractors should demand to be added to the policy as an additional insured and insist the general contractor have a duty to indemnify, even in instances of their own negligence – be aware there are anti-indemnity concerns which I will not discuss within this article. It is unclear how this safeguard would be enforced in the face of a debate on the application of the economic loss rule, but it will undoubtedly assist to protect the subcontractor from liability.

If all else fails and a party finds itself facing liability for a multi-party project, it should be inherent that the plaintiff is limited to recovery for the “independent injury” alleged. Stated differently, if the plaintiff claims it suffered damage to “other property” as to avoid the application of the economic loss rule, it should be limited to recovery of only the damages to that “other property.”

Accordingly, in the example of the window contractor damaging the roof, the homeowner should be limited in its recovery from the window contractor to those damages done to the roof. The window contractor should not be subjected to damages done to other portions of the property solely by way of his inclusion on the jury charge. This issue has not been addressed in Texas courts and its application is unclear.

In these disputes, the owner will likely sue the general contractor for breach of contract along with its cause of action against subcontractors in negligence. This presents a difficult one satisfaction rule scenario because multiple defendants are being pursued for separate causes of action. However, the Supreme Court of Texas recently ruled that the fundamental consideration in applying the one-satisfaction rule is whether the plaintiff has suffered a single, indivisible injury – not the cause of action plaintiff asserts: “There can be but one recovery for one injury, and the fact that more than one defendant may have caused the injury or that there may be more than one theory of liability, does not modify this rule.”[24]

Therefore, plaintiff cannot use craftily drafted pleadings to achieve multiple recoveries for a single injury and avoid the application of the one satisfaction rule.

This recent Texas two-step to avoid the application of the economic loss rule is altering the common pattern of litigation in construction disputes. Contractors can no longer rely upon the benefit of their bargains within the contractual chain. Moreover, it is nearly impossible to protect against liability without contractual privity. This article outlines several scenarios in which a party outside of contractual privity may face full liability for damages. However, the trend continues to grow in the face of Texas courts’ attempt to reasonably apply the Chapman holding.

Undoubtedly, the Supreme Court of Texas will eventually clarify this vague and broad application of the Chapman rule. Until then, parties should ensure they enter contracts with parties who hold sufficient insurance coverage, keep diligent work logs, and contract for a duty to defend and indemnify to the fullest extent allowed under Texas law.

Larry is a founding partner of West Mermis PLLC who is known for his proven courtroom experience in construction and commercial litigation. He has tried cases throughout the State of Texas. For more than thirty years, Larry has successfully represented general contractors, subcontractors, manufacturers, developers, insurance companies, owners and individuals in complex commercial litigation, construction defect litigation, business litigation, insurance defense and worksite accidents.